What's the filibuster and why does Trump want to get rid of it during the shutdown?

News > Politics & Government News

Audio By Carbonatix

12:42 PM on Friday, October 31

By BY SEUNG MIN KIM

WASHINGTON (AP) — Seemingly frustrated by the government shutdown and Democrats' unwillingness to accept a Republican funding bill, President Donald Trump is once again demanding that the Senate eliminate the legislative filibuster.

The filibuster is a longstanding parliamentary tool that halts action on most bills unless 60 senators in the 100-member chamber vote to move forward. Over the years, it has stymied policy priorities for Democrats and Republicans alike, and Trump has been complaining about the maneuver since his first White House term.

Getting rid of it would be a way for Republicans to immediately end the now month-long shutdown, he said. “It is now time for the Republicans to play their ‘TRUMP CARD,’ and go for what is called the Nuclear Option — Get rid of the Filibuster, and get rid of it, NOW!” the president wrote on his social media site Thursday night.

But majority Republicans have strongly resisted calls to eliminate the legislative filibuster, since it would dilute their power if and when they are in the minority again. In its best form, the filibuster encourages compromise and dealmaking.

Here are some common questions about the filibuster, and why it's coming up now in the shutdown debate.

Unlike the House, the Senate places few constraints on lawmakers’ right to speak. But senators can use the chamber’s rules to hinder or block votes. That's what's effectively a filibuster — a term that, according to Senate records, began appearing in the mid-19th century.

The filibuster isn’t in the Constitution and it wasn’t part of the Founding Fathers’ vision for the Senate. It was created inadvertently after Vice President Aaron Burr complained in 1805 that the chamber’s rule book was redundant and overly complicated, according to historians.

But how the filibuster is used today doesn't resemble the public's longstanding perception of the tactic, which was made famous by the 1939 film, “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” in which James Stewart played a senator who spoke on the floor until exhaustion.

Now, senators inform their leaders — and often confirm publicly — that they will filibuster a bill. No lengthy speeches required. Nonetheless, the Senate still needs to muster 60 votes to move past that obstacle. If they get that, then senators can move to final passage, which only requires a simple majority.

Yes, but only for nominations. In 2013, then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., led Senate Democrats in eliminating the filibuster for all nominations except for candidates to the Supreme Court, triggering what's known in the Senate as the “nuclear option.” Democrats were fed up with repeated Republican filibusters of President Barack Obama's nominees, especially to the influential U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Kentucky Sen. Mitch McConnell, then the minority leader, furiously warned Democrats that they'd come to regret going nuclear. And he returned the favor in 2017, when Republicans moved to eliminate the filibuster on Supreme Court nominees as they confirmed Neil Gorsuch to the high court.

Trump mentioned in his Truth Social post that eliminating the filibuster would help Republicans get the “best Judges” and the “best U.S. Attorneys,” but it's unclear what he meant since he needs only a simple majority to install those picks.

Democrats came close to dumping the legislative filibuster for voting rights legislation in 2022, but faced resistance from then-Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia. They said changes to the filibuster would haunt Democrats if Republicans regain control of Congress and the White House — which the GOP did, not long after.

Earlier this year, Republicans changed the Senate's rules further to make it easier to confirm large groups of the least controversial executive branch nominees. But they have resisted calls from Trump to eliminate so-called “blue slips” that allow both senators to sign off on some lower court judges regardless of party.

As with any government funding bill — and most other legislation — Republicans need help from at least a handful of Democrats to clear the 60-vote threshold in the Senate since they control just 53 votes.

In exchange for their votes on a stopgap funding bill, most Democrats have been demanding an extension of subsidies for people who purchase health coverage under the Affordable Care Act. Republicans say that's a costly nonstarter, especially on a bill that keeps the federal government operating for a mere seven weeks.

Democrats argue that because the Senate needs 60 votes to advance funding bills, that gives them leverage. As the shutdown drags on, frustrated Republicans have been floating the idea of getting rid of the filibuster in order to erase that leverage.

“Maybe it’s time to think about the filibuster,” said Sen. Bernie Moreno, R-Ohio, on Fox News earlier this month. "Let’s just vote with Republicans. We’ve got 52 Republicans. Let’s go, and let’s open the government. It may get to that.” (There are 53 GOP senators, but one — Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul — is a committed ‘no’ on funding bills.)

Unlike many other demands from Trump, GOP senators have generally resisted his calls to get rid of the filibuster.

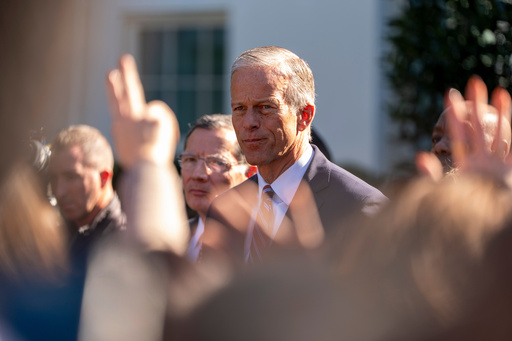

Senate Majority Leader John Thune has long defended the filibuster, and began his tenure as the Senate's top official in January pledging to preserve it.

He reiterated those sentiments in early October, saying the filibuster is “something that makes the Senate the Senate” and that the “60-vote threshold has protected this country.” His spokesman emphasized on Friday after Trump's comments that Thune’s position hasn't changed.

Veteran senators who have seen the chamber swing back and forth from Democratic to Republican control are generally the ones who are the most firm on keeping the filibuster. But even some newer members agree.

“The filibuster forces us to find common ground in the Senate,” Sen. John Curtis, R-Utah, elected in 2024, said on social media on Friday. “Power changes hands, but principles shouldn’t. I’m a firm no on eliminating it.”

Oftentimes, House Republicans weigh in on Senate strategy, urging GOP senators to follow Trump's wishes to eliminate the filibuster. But House members — unfortunately for them — have no influence on what the Senate does.

Speaker Mike Johnson said he texted with the president after Trump’s late-night demand but refused to publicly weigh in on the filibuster question.

“It’s not my call,” Johnson said during his daily press conference at the Capitol.